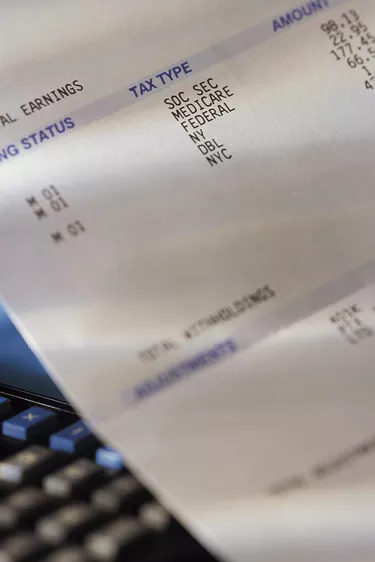

The Old-Age, Survivors and Disability Insurance program is part of Social Security. The federal government charges a tax of 12.4 percent on all wage and tip income. Of this, 6.2 percent comes out of your paycheck in order to fund current Social Security benefits to retirees, survivors benefits to widows, widowers and orphans, and disability payments to those who need them. An additional 1.45 percent comes out of your paycheck each month to fund Medicare. Your employer pays the other half of your OASDI taxes and matches your Medicare tax. Self-employed individuals must pay both the employer and employee contributions to OASDI and Medicare.

History

Video of the Day

Social Security first came into being when President Franklin Roosevelt signed the Social Security Act into law in 1935. The government began collecting taxes in 1937, and the first regular monthly benefits commenced in 1940. It was originally conceived as a retirement program, but survivors benefits were added to Social Security in 1939 and disability benefits were added in 1956. President Lyndon Johnson signed Medicare into law in 1965. Congress passed a cost of living adjustment in 1972, which tied benefits to the rate of inflation.

Video of the Day

Benefits

OASDI pays a portion of former income to qualified retirees. Actual benefits vary depending on how much the beneficiary contributed, and the age at which they elected to begin taking Social Security benefits. The average monthly benefit under OASDI in 2008 was $1,104 per month for retired workers, and $589.60 for spouses of retired workers. The average monthly benefit for survivor benefits was $981.30, and the average payout to disabled workers was $1,063.10.

Tax Structure

The government levies the OASDI tax on the first $106,800 in income as of 2010. Any income received over $106,800 is not subject to the OASDI tax. This means that the tax is regressive. But benefits are regressive too, since lower income workers get a higher percentage of their income replaced by Social Security income.

Challenges

Social Security's biggest challenge is demographic: When the system was first designed in 1935, the average worker only lived a few years beyond retirement age, and only collected benefits for a few years. Meanwhile, a large cohort of baby boomers is soon to reach retirement age and begin collecting benefits, just as a "baby bust" generation is reaching its peak earnings years. The result is that the number of workers supporting a single retiree through their Social Security taxes has fallen from 15 to 1 in 1935 to 3.2 in 2010. That number is expected to fall to 2.2 workers per retiree by the year 2030, according to an analysis from the Urban Institute.

Outlook

Historically, the Social Security system has generally run a surplus: Payments contributed by workers were more than enough to fund current benefits, with all surpluses used to purchase Treasury Bonds within the Social Security Trust Fund. Since the Trust Fund, however, consists entirely of claims on the general revenue of the United States, Congress must make some difficult decisions in coming years, as demographic trends turn the Social Security surplus into an operating deficit. Congress will either have to increase taxes, decrease benefits (perhaps by raising the retirement age), or get better returns out of the Social Security trust fund - a goal which will require privatization in some form, since under the current system any increase in returns is canceled out by an increase in outlays in the general fund of the United States.